Theophilus Ejorh

Publisher: Panda Publishing

Publication Date: 2019

Pages: 69

The first valuable thing about Van Gogh and the Colours of Love is the explanatory introductions for most poems in the collection. The notes are attention-grabbing and provide robust insights into the events, objects, or moments that inspired the poems. They also help the reader achieve a rewarding imaginative appreciation of the poems and a satisfying understanding of their inherent connexion, like fabrics woven into a fine tapestry. Several of the poems were inspired by personal experiences, such as Frisby’s visits to some natural surroundings, his visits to museums and art galleries, observations of some real-life events, such as “a broad-winged hawk hovering over a cliff,” the viewing of his first house, or the memory of a departed loved one, among others.

Though famous and lesser-known works of art provided the ideas for several of the poems, it could only take an individual like Frisby, whose scholarships in Art History and Renaissance and Modern Literature provided him with the intellectual tools to appreciate and translate such artistic pieces into a piece of redolent poetry like Van Gogh and the Colours of Love.

Frisby is perspicacious and sometimes troubled in his observations, especially those unmasking oppressed human conditions. His moments of introspection on the artworks had been stimulating as to spawn such powerful poems as ‘Hunched Upon His Memories,’ ‘That Lamp,’ ‘Hidden Agendas,’ ‘J’accuse,’ ‘Her Unmade Bed,’ ‘Rehearsal,’ ‘Weightless,’ ‘Rasta Christ,’ Gold Teeth and Crucifixes,’ ‘Cave Art,’ and ‘The Meeting of the Waters.’ His encounters with arts also inspired other poems like ‘I see No Colours,’ ‘Churnings,’ ‘But Those Two Soldiers,’ ‘In Dublin’s Unfair City,’ ‘Etruscan Wake at Villa Giulia,’ and ‘Lascaux,’ The brilliance immanent in Van Gogh and the Colours of Love also stems from Frisby’s transportation of the ideas and images from his observations to actual human experiences. The work reflects possible influences by Robert Frost in his proclivity with the natural setting, William Blake in his romantic sensibility, T.S. Eliot in his disillusion with the failure of modern civilisation, and Seamus Heaney in his critical realism, described as realism that maps the ontological quality of social reality or produces experiential facts and events. Whatever the influences, Frisby’s ability to draw on visual arts and forge redolent poetry that speaks to the realities of the human condition, personal relationships, the harmony or breach of the natural order, is sublime. He forges a personal style in Van Gogh and the Colours of Love, drawing on historical motifs (some dating to the Renaissance) to capture the complex nuances of modern life and society, but speaking to critical issues of existence and universal realities, such as oppression, war, bloodshed, poverty, social injustice, death, misery, love, and beauty.

In his W.D. Thomas Memorial Lecture delivered at University College of Swansea, Heaney (1993) emphasised poetry’s burden to be transformative in its espousal of reality that surpasses the conditions it observes. In essence, poetry should be committed to changing the social condition. Frisby’s book seeks to achieve that.

The second part of the book’s title, the colours of love, seems ironic and deceptive. At first glance, one anticipates an encounter with numerous poems provoking shades of deep affection – warmth, fondness, intimacy, care, devotion, and feeling of humanity. Instead, what the poet feeds the reader is troubled modernity and a fraught universe, both characterised by power, authority, perdition, struggles, conflicts, wars, betrayal, lies, and man’s inhumanity to his fellow man. Perhaps, Frisby has chosen ‘the colours of love’ satirically to expose modern civilisation’s failure to live up to its promises with this work. Except in a few poems like ‘Darkling Blue,’ ‘That Lamp,’ and ‘Weightless’ (in which a mother grieves the death of her beloved son in her hands like Mary grieving her son Jesus’ crucifixion), there is hardly any other poem in the collection that exudes a sense of love.

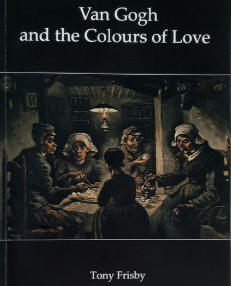

In ‘Darling Blue,’ there is sensual love between the speaker and his mistress, whose “silky warmth/informs my touch.” As the “night inflames” the speaker’s “imagination,” and both lovers encounter a moment of shuddering ecstasy as of clouds “scudding the sea’s moist canvas.” Though the poem tries “to evoke the texture and colour of love,” as its descriptive notes say, a more profound, symbolic appreciation suggests a sensual encounter between lovers. In ‘That Lamp,’ a poem inspired by Van Gogh’s 1885 painting, ‘The Potato Eaters,’ and possibly the catastrophic Great Irish Potato Famine (1945-1949), a peasant family gathers daily by a single lamp to eat a meagre meal. Amidst the tragic situation, the lamp is a source of illumination in the household whose members radiate pure filial love, devotion, solidarity, and a deep sense of emotional attachment that binds them together:

So, there is love too; in every glance,

every gesture and smile

in each and every shaft of light,

in all those sad, knowing brushstrokes.

The poem ‘I See No Colours’ perhaps accentuates the feeling of often absence of true love in the human experience. The natural surrounding lacks vitality and beauty, as “the bay stretched bleak and muddy grey.” However, in an artist’s 1950s February painting of the Atlantic at St. Ives in Cornwall, nature is magnificent and bathed in the colours of beauty, “whites and reds and blues” and “streaks of yellow surf/hinted the coming of spring.” An angry passer-by scoffs at the painting: “I don’t know where you get your ideas from/…I see no colours there.” Here, one understands the passer-by’s frustration with an artist’s attempt to idealise nature, thus his inability to relate with the painting, which fails to match the bay’s dreariness and greyness, the physical environment, symbolising wider human sufferings and misery. Therefore, in the world of reality, there are no colours of love anywhere, be it the wider universe or its troubled societies. Ideally, the colours of love are sublime rather than visual or physical because pure love is transcendental, refreshing, and uplifting. This is the deeper understanding of the poem.

One cannot but applaud Frisby’s power of contradictions in the work. He balances the ugly with the beautiful, pain with pleasure, misery with cheeriness, in a way that speaks to the mystical character of existence marked by antithetical realities, an intersection of opposites that mutually reinforce each other in a functionalist manner.

The work seeks to find meaning and order in commonplace objects, events, and experiences. Frisby demonstrates love and sympathy towards ordinary people in a Blakean sense. He seems frustrated and disappointed by modern capitalism’s failure to improve the condition of ordinary people.

In ‘In Dublin’s Unfair City,’ perhaps a pun on Irish television drama ‘Fair City,’ one witnesses a city in stasis: “Nothing changes; not the past/the present or the future.” The same cycle of depressing historical realities has subsisted since the Vikings invaded Ireland, pillaged its monasteries’ treasuries, trampled its religious sensibility, and the English inhumane colonial rule. Today, as native free-market capitalism tightens its stranglehold on the country, Dublin remains a city still stuck in the cage of its past. Frisby’s attack of the new capitalists’ oppressive and acquisitive spirit is Juvenalian – morally indignant and frustration-laden. The Dublin of the Vikings and the English colonialists has given way to a modern city with new forms of oppression, “another bout of rape and pillage/another raid by gold-plated long-boats/of the corporate world, gliding silently again.” In its stasis, “the same undiminished appetite/for wealth and power” holds sway in the city. Capitalism is about the contradictions between the richness of the ruling class and the poverty of the teeming poor. Frisby vividly deploys this antithesis in the last two stanzas of ‘In Dublin’s Unfair City’:

Christmas glitters in every puddle

and beggars wear the wearied eye of hunger;

on Stephen’s Green a scald crow

dines on Irish fat worms.

Haunting realism runs throughout the book. In ‘Gold Teeth and Crucifixes,’ the Duke of Urbino funds his charitable art projects with the immense wealth he has amassed during his career as a ruthless mercenary. He also holds an ignoble record of showing no mercy to individuals he conquered. Disturbing images dominate the poem: there is the “splash of blood-red poppies” in every hill, “unwitting reminders/of mercenaries steeped in gore,” even as “crucifixes” are forged “from the gold teeth of the slain.”

In ‘But Those Two Strollers,’ the failure of modernism, which T.S. Eliot earlier captured in The Waste Land, and W.B. Yeats in ‘The Second Coming,’ is powerfully depicted. In the poem, inspired by ‘The Scream,’ an 1893 painting by Edward Munch, one perceives the horrors of inhumanity as an African refugees’ boat flounders in the turbulent Mediterranean. The description of the turbulent experience is penetrating with its ghastly anthropomorphic metaphors as in “tortured sky,” “the lifeless sea,” “sickly hills,” and “barren, treeless landscape.” Frisby’s images of a moribund natural environment provide the basis for the boat’s floundering as the refugees scream fruitlessly for rescue to two strollers who merely sigh while observing the tragedy. Disappointed, the poet asks rhetorically about the strollers: “Do they not hear that scream/…as the world hurtles towards its first modern muddy blood-bath?” The final stanza of the poem links the tragedy in the Mediterranean to broader modern-day experiences of oppression and racism in society:

And what of now; this now of newly polished jack-boots,

Coiffure racism, and bridge-burning outpourings?

And there still strollers who cannot hear our screams of terror

As this newest century turns, once more, upon an evil axis?

In the poem ‘Cave Art,’ the speaker, “alone and terrified,” encounters a “brave new brutal world/of demi-gods and oligarchs.” It is a world ruled by “gung-ho leaders/who speak of right, might and power/but have no kindness.” Again, this reflects hypocrisy marking modern politics, whereby most political pledges of social transformation often do not translate into reality. Essentially, the human world is a “troubled globe” of “terror” and “mounting fears.”

The beauty of Van Gogh and the Colours of Love lies in its deployment of powerful imagery, arresting symbolism, and emotive diction. Frisby chooses his diction to provoke pervasive images of suffering, pain, misery, and death. In ‘Hunched Upon His Memories,’ one encounters the Quirinal Boxer in medieval Roman. He is a “muscled killing machine,” suggesting the boxer’s reputation for murdering his opponents in the arena. Now mellowed by age and time and “longing for death,” he glares at the world “through emptied eyes.” There is an irony about the reality of human mortality here, the transience and end of life. How did time and age temper the boxer, a once invincible killer, as he grapples with his mortality?

The sense of mortality occurs in other poems, such as ‘Etruscan Wake at Villa Giulia,’ in which the dead happily “smile/at the prospect of eternity,” as they “drift across the Styx,” the gulf of transition. In ‘Dress Him as You Will,’ the speaker effuses in the opening line, “Death is death is death.” The certainty of death is evoked in the confirmatory diction. Death is

an end, a final milestone reached,

a blip, end-stop, a hitch, a glitch in time,

a measured span, measuring less

than one stitch

in the eternal tapestry of life.

In ‘Gold Teeth Crucifixes,’ the image of death is provoked by the “splash of blood-red poppies,” which are vivid reminders of the slain, symbolised by poppies. One understands the poppies in the symbolic sense as representing the victims of ruthless killings. The mercenaries are “steeped” in the victims’ “gore,” a word that evokes and signifies violence and bloodletting.

Frisby employs repetitions in relevant places for emphasis and catchiness. There is a repetition of “death” in ‘Hunched Upon His Memories’ to affirm life’s impermanence, the boxer’s impending mortality. There is also a form of epizeuxis (or palilogia), the repetition of a single word in succession in a poetry line to give added emphasis or intensity and passion to the repeated word or phrase. Such repetitions occur in the opening lines of poems, for example, “Joy is joy is joy” (‘Hidden Agenda’), “War is war is war” (‘J’accuse’), “Stone is stone is stone” (‘Weightless), “Death is death is death” (‘Dress Him as You Will’) and the poem of the same title ‘Lies are lies are lies.’ This form of repetition gives the poems certain musicality. Frisby also deploys devices like onomatopoeia deftly. For example, there are the “babblings,” “heaving plops,” and “oozy burblings” of the river. The River Suir also “babbled and blathered/in school holidays,” reflecting the tension in the natural environment. These literary devices are complemented by the sustained use of enjambment (run-on lines) in the entire collection. By allowing his thoughts to run over lines without a grammatical pause, Frisby creates complexity and fluidity in his thought processes, heightens tension, and achieves pace and momentum in his poetry.

Van Gogh and the Colours of Love is a masterly work of poetry by a master artist. The book is intellectually rewarding, provokes powerful feelings and images, and speaks to broader universal issues of human existence and relationships.

References

Frisby, T. (2019). Van Gogh and the \Colours of Love. Brighton: Panda Publishing.

Heaney, S. (2993). Joy Or Night: Last Things in the Poetry of W. B. Yeats and Philip Larkin, W. D. Thomas Memorial Lecture. Swansea: University College of Swansea on 18 January.

Theophilus Ejorh is an award-winner writer and the author of the novel, Till Dawn Comes With a Song. He holds a master’s degree in English and a Ph.D. in Sociology.