By Jeff Ukachukwu

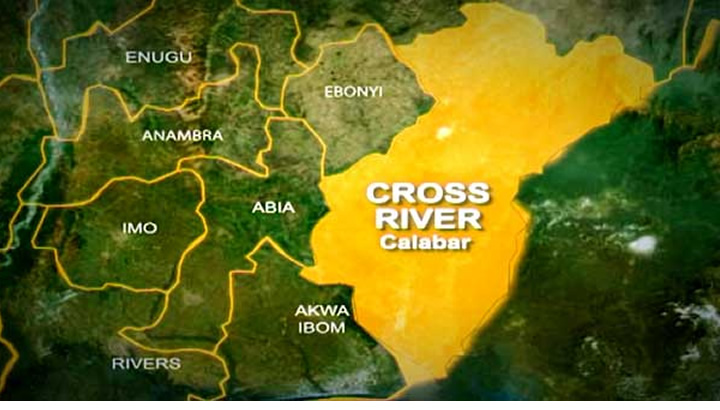

When the earth was first broken at Adiabo on 10 April 2025 for the Special Agro-Industrial Processing Zone, one could almost feel the weight of years of planning to settle into that moment: a 130-hectare promise backed by a US$538 million investment from AfDB, IsDB, IFAD, the Green Climate Fund and the federal government, aimed at transforming Cross River’s agricultural potential into tangible industrial activity.

At that ceremony, Vice President Kashim Shettima and AfDB President Akinwumi Adesina stood amid hopes that the zone’s dedicated power connections, Agro-Transformation Centre, and links to Calabar and the forthcoming Bakassi Deep-Sea Port would finally provide farmers and processors with a dependable launchpad into larger markets. There was a collective sense that this was more than a ribbon-cutting—this was an inflexion point in the state’s long journey from subsistence farming toward export-oriented value addition, underlining the significant impact of these projects on the state’s economy.

Yet the vision extends far beyond that single site. The revival of the Ikom Cocoa Processing Factory, announced in February 2025, exemplifies how Cross River is attempting to revive dormant assets: officials project creating some 5,000 direct jobs and nearly $6.8 million in annual value once financing is secured and operations resume.

This effort feels emblematic: cocoa has long been a mainstay of many smallholder livelihoods here, but without local processing capacity, farmers struggled to capture more than a fraction of the crop’s final value. Restarting that factory is a statement that raw commodity exports are no longer enough; the aim is to retain a greater share of profits within the state, foster skills in processing, and anchor supply chains that link Ikom’s hinterlands to ports and beyond.

Rice, too, has become a marquee ambition. In April 2024, Governor Bassey Otu inaugurated the 50,000-hectare Ndok–Ogoja farm with a bold credit scheme injecting ₦150 million monthly to catalyse production. Already, the farm feeds a 10 tonnes-per-hour vitamin-enriched mill commissioned in May 2023, and plans are underway to double that capacity by 2027.

This scale-up is not mere showmanship; it reflects lessons that securing consistent raw material supply is essential to keep processors humming and that large-scale farming when paired with out-grower models, can reduce the boom-and-bust cycles smallholders face. At the same time, warm reflections from farmers suggest cautious optimism: the credit support removed a significant barrier, but questions linger about inputs, irrigation, and market linkages beyond the immediate mill.

Perhaps most surprising to outsiders is the cultivation of wheat in a rainforest state. Following Cross River’s designation as the first wheat-producing state in southern Nigeria in October 2024, demonstration plots were established in Obanliku and Obudu, with dry-season schemes launched by the federal government.

This development reflects the evolution of agronomic research and farmers’ willingness to experiment: the irrigation infrastructure under the Cross River State-Wide Irrigation Infrastructure Development (CRSWIID) project promises to transform idle months into productive seasons, challenging the notion that wheat is exclusive to the north. Yet farmers candidly note the novelty brings steep learning curves, from seed varieties to post-harvest handling, reminding policymakers that technical support and market development must walk hand in hand with field trials.

In August 2024, the inauguration of the eight-tonnes-per-day cassava mill in the Idoma community signalled a similar shift in staples processing, promising around 1,000 direct jobs and anchoring a 15-hectare nucleus farm nearby.

This model under IFAD’s LIFE-ND programme embodies how small- to medium-scale processing hubs can be replicated across LGAs, offering local farmers a nearby market and generating income that circulates within communities. Anecdotes from cooperative leaders reveal pride in seeing cassava tubers transformed on-site rather than being sent elsewhere; they also underscore the need for reliable power and efficient logistics to ensure the mill operates at capacity rather than idling intermittently, highlighting the crucial role of the community in these projects.

The Calachika integrated poultry complex at Ayade Industrial Park, with the capacity to process 24,000 birds per day, is a significant step in Cross River’s protein production. As it undergoes test runs and pursues NAFDAC approval and halal certification by 2026, it is clear that linking the poultry farm to processing within the same park reduces transport delays and enhances biosecurity. However, the facility’s success is contingent on addressing regular issues such as powering the facility and ensuring a steady feedstock supply, which remain key discussion points at stakeholder meetings.

Underpinning these big-ticket projects is a quieter revolution in data and inclusion. The launch of a state-wide digital soil-fertility map in early 2025 offers GPS-level guidance on what to plant where, a tool rarely seen in Nigeria’s South-South region. Such information, when combined with extension support, can help farmers shift from guesswork to precision, tailoring inputs to soil types and reducing waste.

Meanwhile, LIFE-ND’s work has supported hundreds of agro-businesses incubates: in Cross River alone, some 286 enterprises were established, yielding over 14,800 tonnes of produce, ₦4.74 billion in income, and more than 2,158 jobs for youth and women between 2023 and 2025. These figures hint that beyond megaprojects, grassroots initiatives are building resilience and diversifying livelihoods, from mini-tractor services to digital extension and savings groups.

Despite progress, friction points remain ever-present: power supplies in northern senatorial zones can falter when mills and cold rooms need them most, and feeder roads often wash out in the rains, disrupting the movement of produce to hubs. Farmers recount nights spent storing tubers or grains longer than planned, worrying about spoilage when transport fails.

Legacy plants in other sectors, such as noodles or timber byproducts, stand as cautionary tales: ribbon-cutting ceremonies once promised revitalisation but stalled when governance, maintenance funding or market alignment proved insufficient. These reminders underscore that building an agro-industrial ecosystem requires not only infrastructure but also robust institutions, clear regulations, and consistent public-private dialogue.

Looking ahead to 2027, the mood is one of determined optimism tempered by realism. Completing SAPZ utilities and securing anchor tenants for cocoa grinding, cassava starch, and expanded rice milling will test coordination among state agencies, financiers, and investors. Enacting and enforcing the new Produce Law, with its focus on traceability and quality standards, must move beyond gazette pages to field inspections and farmer education.

Scaling irrigation for wheat and dry-season rice under CRSWIID holds transformative potential, but only if water management systems are reliable and maintenance plans are funded. Fast-tracking financing for SMEs in LIFE-ND clusters could democratise processing capacity, yet it requires streamlined credit mechanisms and technical backstopping. Finally, synchronising the Bakassi Deep-Sea Port timeline with bulk commodity export strategies will determine whether Cross River can truly deliver “forest to factory to foreign exchange,” turning lofty slogans into addressable coordinates on the map.

Ultimately, what stands out is not just the infrastructure or the numbers but the evolving mindset—a recognition that agriculture in Cross River must transcend subsistence, embracing data, processing, and market orientation. Farmers who once viewed crops as a seasonal means of survival now speak of enterprise, quality premiums, and export prospects; entrepreneurs weigh processing investments against the availability of raw materials and energy costs.

The path remains uneven, strewn with practical hurdles and occasional delays, yet the collective movement—from digital soil surveys to mechanised rice farms, from cocoa factory rehabs to community cassava mills—signals a state grappling earnestly with its comparative advantages. If the next two years see these projects mature into stable operations, Cross River may well rewrite its economic narrative, proving that even rainforest states can harness agribusiness as a driver of inclusive growth and job creation.

Dr Jeff Ukachukwu is a public affairs analyst and writes from Calabar