By Adewale Adeoye

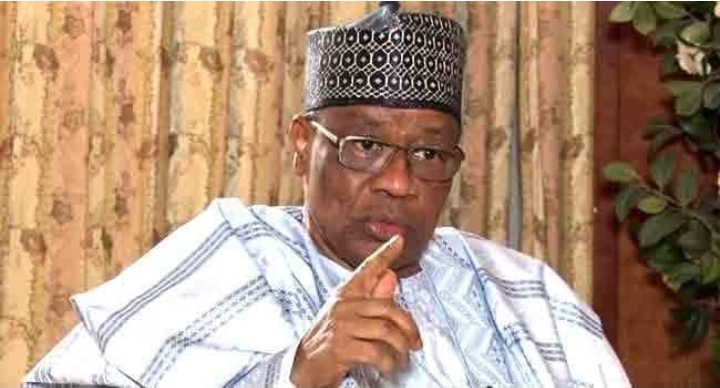

It does not matter if the thoughts of former Head of State General Ibrahim Babangida in his 398-page book with 13 chapters were written by him or his hired cronies. What matters is that he has owned up to every word. In this book, he attempted to tell his own version of the sordid history of Nigeria. It is a mark of courage, courage that arose out of the fact that the country has remained in the firm grip, and under the trample jackboots of a trend Babangida himself represents.

It is an attempt by the oppressor to narrate and justify the travails, the pangs, pains and anguish of his helpless victims. Though he claims to discourse his personal intervention in the affairs of the country, but it is also an event in which we were eyewitnesses and in a position to agree with or dispute claims. It is our collective history, not just about him.

No doubt, Babangida is a man who defined the many ugly curves of Nigerian history, a man whose claws are felt in every strand of the social, economic, cultural and political spectrum of Nigerians, at least for seven years and beyond. Let us face it. There are important notes in his treatise. We should explore the truth told by the dictator before exploring his veiled contempt and dust of lies.

He said in the prologue ‘Over three decades have passed. Though I have been out of formal office for the period, I never exited national service for one day….. I have, therefore, remained on duty for Nigeria round the clock.’ He is right. He has struggled over the years to ensure his tendency controls political power in Nigeria, at least at the centre. To a large extent, he won.

To be precise, since 1966 when the military seized Nigeria at gun point, the country has been at the mercy of just eight individuals, all of them soldiers: Generals Yakubu Gowon, T.Y Danjuma, Murtala Mohammed, Mohammadu Buhari, Olusegun Obasanjo, Ibrahim Babangida, Sani Abacha and Abdulsalami Abubakar. Out of these individuals, all, except one, had been President or Head of State while two of them ruled Nigeria twice. They are all conservatives, if not reactionary while radical element(s) that rose among them, like Murtala were thrashed.

These few individuals, in their caucus meetings since 1966, have produced the military Heads of State of civilian Presidents of Nigeria, without allowing a paradigm shift.

They produced Shehu Shagari in 1979, Ernest Shonekan in 1983, Obasanjo in 1999, Musa Yardua in 2007, Goodluck Jonathan in 2009, Buhari in 2015. I believe they lost out in 2023, having divided their loyalty between, perhaps for the first time in Nigerian history. If they had united around one candidate, they would have won again. So, since 1966, Nigeria has largely been ruled by the same political culture, at least at the centre. It was Babangida that extended the capture of the centre to states when in 1991, he banned progressives from participating in his ill-fated transition at the Federal and State levels.

Consequently, the message from Babangida is that even though he left office in 1993, he is in power by proxy. He is entrenched in the context of the fact that his philosophy of governance, driven by waste, corruption, repression, exclusion and treasonable felony against the masses remains the most dominant trend in public administration today. It should be understood that the reactionary leadership of Nigeria has its own military, political and economic wings.

Nothing demonstrated this fact more than the presence of the top echelon of the military, political and economic ruling class who control the commanding height of the Nigerian economy, business icons whose wealth are not from expertise but rather based on their access to undue, cheap favour, at the book launch, and the huge donation of over N17b as compensation for Babangida’s leadership, albeit, for his crimes against humanity. But no one is thinking of N100m for victims of Babangida’s repression.

The donation also shows that the money in the hands of individuals is enough to offset Nigerian external debts. In this case, N17b was just free money for an individual. Ironically the funds donated has never been realised before, in any single donation for a public medical centre or a public library in Nigeria.

This shows the unity of purpose and the interchangeable variables between the economic, military and political class in Nigeria, being one but appearing in various forms and shapes, deceitfully, while retaining its fundamental ground norm of exploitation.

Those who gave the money were also, in their own right, performing a national duty in honour of someone who created the rot from which many of them feasted and continue to line up for their buffet.

The economic and social downturn of the country though exterminates the majority of the people, pouring on them showers of misery and deprivation, yet, it is from this decadence that many rich people derive their wealth. The Nigerian ruling class is so naive that it lives under the false assumption that radical change that may consume them is impossible even in the face of potential upheaval that stare Nigeria in the face.

The publication of that book shows that Babangida is a symbol of a long lasting infamy in Nigeria.

Another truth. On why he delayed the writing of the book, he said ‘It was necessary to allow a cooling off period so that the generation that witnessed our days in office would have had time to reflect, to experience other administrations, and be in a position to situate our contributions correctly.’ He was right to the extent that since he left office, successive governments have refused to hold him accountable for his heinous crimes against truth. So, in terms of the justice system since he left office, public accountability remains a mirage. He also stated that over the years, memory has ‘dimmed, and recollection may have lost acuity.’ Perhaps, this statement is a veiled admittance of two things: Many Nigerians suffer memory loss and could hardly recollect the atrocities Babangida represented. Some who remember, have been recruited or absolved by the system to the extent that they can even deny their sisters were never raped.

Secondly, his own memory is only half awake. Truly, his memory has failed him in many of his recollections. He may not recollect how he said on NTA that ‘We are the masters in the act of violence’ in the heat of the 1993 riots. He certainly would not remember the killing of over 30 people in one day on Ikorodu road in Lagos, the dumping of many bodies in the Lagos lagoon.

The celebration of Babangida’s ‘Journey in Service’ is the victory of the oppressors over the oppressed, the triumph of evil over good. Though the adoration of hooliganism in governance, the sustainability of repression, exclusion and the glorification of mental torture Nigerians have endured for decades, yet the victory over us, at the fullness of time, is temporary, pyrrhic.

If there had been a revolutionary intervention in the politics of Nigeria, Babangida would either be in jail or would be too timid or cowed as to come out bare-chested to poke the nose of his victims.

After reading the book, I realise that the content lacks ideological depth even with the conscious attempts to cover his iniquities with flowery language.

He glossed over very important historical issues like the resistance against him even within the military, the civil war and also about the April 1990 military coup led by Major Gideon Orkar.

He ignored the reason behind the excision of the core-Fulani states whereas, it is a known fact that the coup was a bloody confrontation with his leadership on the National Question which earlier motivated the Col Buka Dimka coup in 1976, an issue that is now naked, right in our very eyes, today, as the country battles separatist insurgency.

Babangida leaves us with the false impression that he loves Nigeria as a ‘nationalist.’ Reading ‘Justice for Sale’ by Major Debo Bashorun, Babangida’s former aide, leads to greater understanding of how Babangida polarised the Nigerian army along religious and ethnic fault lines for his own strategic, yet defeatist tactics of survival.

Babangida was also silent on many critical issues of human right violations under his tenure. His regime unleashed one of the worst right abuses on the students movement while he was responsible for the deaths of hundreds of innocent students apart from creating the nursing bed for violent cultism on Nigerian campuses.

I recall 1986 and 1987, the years of clubs, daggers, guns and knives. Four students of the Ahmadu Bello University had been killed after his government ordered ‘Kill and Go’ police to invade the campus. The invaders raped and killed some students. It became a national upheaval. At the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, we joined the national resistance.

I was in the leadership with the late Emma Ezeazu and Chima Ubani. The IBB regime recruited students, trained and armed them. Their duty was to attack, kidnap and maim students’ leaders. At Eni Njoku Hall, where we were having our rally, four students led by a student, now in exile in the Philippines, stormed the venue and kidnapped a student, Lanre Ehonwa.

Not satisfied, that night, they stormed the hostel of Chidi Omeje and Kunu Harmony, two radical students. They maimed them. They did the same at Nigerian University campuses. Many of these students were later recruited to join the State Security Service. At least I saw three of them later in years, who made the confession.

At the University of Benin, with the help of IBB’s secret service and the recruited students, they bundled ASUU leaders out of their homes in broad day light. At the University of Ilorin, over 30 lecturers were sacked. In ABU, Patrick Wilmot was arrested and deported from Nigeria. Many students died as indirect victims of Babangida’s rage. After a solidarity rally at UNN in 1987, I recall with pain, how no less than five students perished on their way back to Bayero University, in Kano including the then speaker of the Students union.

What about hundreds of students expelled and who never completed their studies? What about the kidnap of Omoyele Sowore and his being injected with poison by sponsored armed men? What of Igboku Otu that was stabbed to death by an unknown assailants one evening in his private Ikeja home?

Babangida forgot the Oko Oba killings of eight people from the same family by his policemen after a protest in Lagos.

He forgot about the murder of the Dawodu brothers and hundreds of people shot dead in the wake of anti military protests. His memory failed him on the disappearance of people like my friend and colleague in The Guardian, Chinedu Offoaro, Prince also of The Guardian, the murder of Tunde Oladepo, Taiwo Lukula and many others across the country as consequences of the successors he bequeath. Oladepo was killed in the presence of his family. They took away his suits. On the day of his burial, the killers came, putting on the suits they had stolen from their victim. They audaciously starred at Oladepo’s wife who was caught by awe and trembling. He fled the country. How do we explain the controversial accident that led to the death of ASP Dare who was investigating the death of journalist, Dele Giwa? Can we easily forget the torture of many soldiers like Digifa Werenipre, now leader of Egbesu Assembly, my friend who was kept in underground cell in Kano? What of Col Gabriel Ajayi who was kept in the cemetery for many years, only to be released to the hands of harrowing, cold death? How can one forget Major Nya and others that I met while I was in detention at the Directorate Military Intelligence and reports that people were being shot and taken away for burial in secret places having been picked on the road on suspicion of being anti-government?

Babangida militarised the mentality of Nigerians through his adoption of violence and brute force over logic and clear thoughts.

Under Babangida, state terrorism was elevated and idolised.

The people soon began to adopt violence as personal norm. The militaristisation of values, of culture, of politics, of debate, of the family, of the mental state finds expression in the current culture of violence in Nigeria today.

The impact is sociological genocide unleashed on Nigerians making the people lose their sense of humanity and the agelong culture of peaceful means of conflict resolution.

However, for me there are interesting takeaways I found in Babangida’s book: There is no organised opposition to the systemic destruction of Nigeria. The people agonise but fail to organise.

The only opposition we have is within the ruling class itself which keeps reinforcing the illusion of dissent. That dissent is only to the extent of giving a semblance of democracy to the outside world, but in form and content, are little different from the force they claim to oppose, and are ready to compromise, to safe the system. Nigeria and its ruling class are weak and fragile, only holding on to straws, but there is no alternative force, strong enough to bring it down. Unless the Nigerian opposition is organised, beyond press statement rhetoric, the oppressors will continue to determine the narrative and even dominate our history and what looks like a curse, will become generational. It is a shame that more than three decades after Babangida left, there is not comprehensive documentation of this fiasco.

Second takeway is that Babangida has once again dismissed the notion that he is a Yoruba man from Ogbomoso. He is also not Nupe. He says it’s a myth. He stated the origin of his Fulani father from Sokoto who later migrated to Minna.

I once encountered this in 1992 as a Defence Correspondent. He had sent notes across military establishments stating his origin from the Sullubawa of the Bagwatse stock in Sokoto.

The third lesson is that Nigeria is governed by devilish principalities, of which Babangida is just a symbol. It means that dealing with the IBB phenomenon demands a class perspective. He only represents a vicious, reactionary group, a tendency that remains dominant in Nigeria. The fourth lesson is in the realm of spirituality. Former Head of State, Abdulsalami said at the book launch that a prophet met him and IBB when they were barely nine years old and predicted that Babangida would be Head of State of Nigeria. It came to pass. It means the world is ordered by a supreme being before who we stand in awe; the world and events have their own supreme author and finisher. Does that mean evil was deliberately imposed on Nigerians by God?

No. I do not think so. My judgment is that God chooses people to lead. He gives people the opportunity to make a difference in the affairs of mankind. He would not come down to run the government on behalf of the chosen. He has given mankind the freewill. It is left for the appointed to manage or destroy the opportunity. That foretold vision, at the same time, also showed the limits of human spiritual prowess.

For instance, the prophet saw Babangida becoming the Head of State, but he did not see Abdulsalami, at least from the latter’s account, eventhough both were together at the time. The prediction gave Babangida a golden opportunity to become a world class hero. He bungled and burnt that opportunity. He disappointed God. He failed mankind. Now, he has no second chance to redeem his battered image either in heaven or on earth.

Adeoye, a multi-award winning journalist writes from Lagos