By Owei Lakemfa

WHEN the old or those who play the role of elders die in Africa, we do not weep. Rather, we celebrate them because they merely transit from the physical to the pantheon of ancestors who watch over the living. Three elders who led the struggle for a better humanity transited within three days this month.

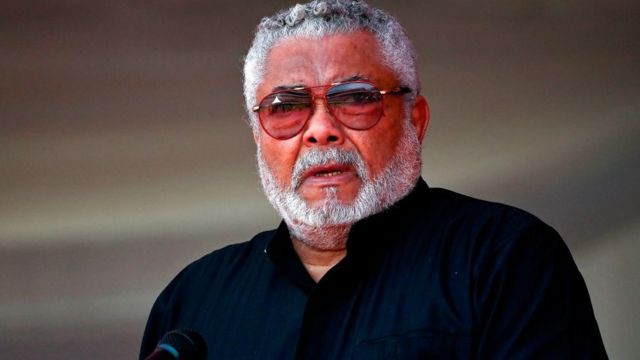

First was Saeb Muhammad Salih Erekat, the dignified burning torch of the Palestine who exited from Jerusalem in the Palestine on November 10, 2020, falling not to the firepower of the Zionists, but to the forces of COVID-19. The next day, Balarabe Abdulkadir Musa the uncompromising champion of the poor, took his leave from Kaduna, Nigeria. Twenty-four hours later, John Jerry (Junior Jesus) Rawlings, the fearless African lion also fell to COVID-19 in Accra, Ghana.

Erekat was one of the most unique beings that walked on mother earth. He doggedly negotiated peace with the Israelis who are only interested in taking more Palestinian lands and annihilating the Palestinians. In the process, he worked with American facilitators whose primary interest is to back Israeli genocide and conquest of the Palestine.

Erekat was Chief Negotiator of the Palestinians, a people who can see that the peace process is dead and that neither the Holy City of Jerusalem which breastfed their indigenous ancestors nor their undisputed city of Bethlehem which welcomed Jesus Christ into the world, can resurrect it.

But until his last breath, Erekat never gave up. He tried to convince all humanity that the Palestine is big enough to accommodate the Judaists, Christians and Muslims. That the Palestine can be a secured home for the original Jews of Father Abraham, the indigenous Palestinians, native Arabs and the returnee Israelis.

If the dead could speak, as he was being lowered into the grave in Jericho, Erekat, a prince of peace, would have urged us all never to give up because the earth is for humanity to inherit.

Rawlings was a sort of negotiator, but unlike Erekat who used words, he employed bullets; where Erekat depended on persuasion, Rawlings was like Shango, the god of Thunder who you are compelled to love. He was a 32-year-old Flight Lieutenant when he attempted to overthrow the Akufo military regime.

However, while being tried for the failed coup, his supporters carried out the June 4, 1979 coup. Rawlings was sprung from jail and appointed the head of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council, AFRC.

He lined up three former military heads of state, Generals Akwasi Afrifa, Ignatius Kutu Acheampong and Fred Akuffo; former Foreign Affairs Minister, Roger Joseph Felli; former Border Guard Commander, Major General Edward Kwaku Utuka; former Army Commander, Major General Robert Kotei; former Air Force Chief, Air Vice Marshal George Yaw Boakey; and former Chief of the Navy, Admiral Joy Amerdume; found them guilty of corruption, and despatched them to heaven to stand on Judgement Day.

Rawlings handed over power to elected President Hilla Limann in September 1979, but overthrew him on December 31,1981 to begin his second revolution. However, he was like Ogun, the fiery Yoruba god of Iron who when angry, is a double edge sword cutting all sides, including enemies and allies.

In 1982, a plot by British special forces in collaboration with the Nigerian government to invade Ghana and overthrow the Rawlings regime leaked. The progressive forces in Nigeria circulated leaflets across Nigeria exposing the plot which was subsequently aborted.

The only time I met Rawlings was as a reporter in 1986 covering the opening ceremony of the Organisation of Africa Trade Union Unity, OATUU, conference. He came in military uniform with his trade mark dark glasses. He rushed through his prepared speech and then threw it aside saying: “That was what I was asked to read.

But let us talk as brothers.” It was an international audience he could not resist. For another two hours, Rawlings spoke extempore, explaining himself, the revolution, his mission and the way out for Africa. His voice rose and sank, only to fire off again. He seemed a man pained trying to explain himself. At other times, it was a tirade.

At the end, he shook hands with us and we took a group photograph. In that photograph, was Rawlings, and a future President of Zambia, Frederick Jacob Titus Chiluba, who was then Chairman of the Zambia Congress of Trade Unions, ZCTU. When I returned to my hotel room that day, I wept.

I had thought Rawlings held a lot of hope for Africa, but the man I watched unscripted for about three hours seemed oscillatory and his position on issues, perfunctory. But I had no doubt he was a patriot, even a pan-Africanist.

The following year I went for another OATUU programme in Accra with my comrade and fellow journalist, Kayode Komolafe. Given the close contacts between the Nigerian and Ghanaian Left, Komolafe called Kojo Tsikata, then Head of National Security.

Tsikata, a former Captain, was close to African liberation fighters like President Samora Machel of Mozambique. He had also joined the army of the Agosthino Neto-led People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola, MPLA, which fought for the liberation of Angola.

Komolafe felt we could go see Tsikata and discuss the situation in Ghana, especially given reports of some comrades being purged, detained or fleeing into exile. The latter asked for our hotel and room numbers and promised to visit. Tsikata came and we had discussions on the direction of the revolution in Ghana and arguments about the Rawlings policies and programmes.

We felt an obligation to see Tsikata off. As we entered the busy lobby of the then Tulip Hotel, the whole place went silent. People seemed to freeze seeing Tsikata.

When we were returning to our rooms, the entire eyes in the lobby seemed to follow the steps of Komolafe and I. We had not realised how big Tsikata was, and were later to learn that he was not only the defacto Number Two in the ruling Provisional National Defence Council, PNDC, but was more feared than Rawlings.

That night, I told Komolafe, we have to change our rooms as anti-Rawlings forces may regard us as legitimate target. Rawlings was to transit to an elected president and even in retirement, remained an enigma.

Balarabe Musa was unlike most Nigerian politicians, a man of principles who despite his privileged position of being Governor of old Kaduna State as far back as 1979, refused to take part in the free-for-all looting of the country’s resources. He held firmly to principles and refused to join any ruling party.

He stuck to pro-people progressive parties even when they stood no electoral chance. We bid these kindred spirits, safe journey as they join our radical ancestors.